Bollywood likes to believe stars endure because of reinvention, but longevity is more often sustained through emotional repetition. Few careers illustrate this better than that of Shah Rukh Khan, and few recurring names in Hindi cinema have carried as much symbolic weight as Rahul. Over the years, Rahul became less a coincidence and more a carefully reinforced emotional identity—urban, aspirational, conflicted, and tailor-made for a rapidly changing India.

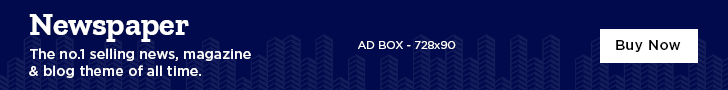

When Shah Rukh Khan first appeared as Rahul Mehra in Darr, the name was anything but romantic. This Rahul was obsessive, unsettling, and dangerous, proving early on that the power lay not in the name itself but in the actor’s ability to imprint it with intensity. Yet what followed over the next decade quietly transformed Rahul into Bollywood’s most recognisable shorthand for modern romance.

That transformation became clear with Dil To Pagal Hai, where Rahul emerged as charming, emotionally evasive, and unmistakably metropolitan. By the time Kuch Kuch Hota Hai arrived, Rahul Khanna had evolved into a cultural prototype—English-speaking, casually privileged, emotionally articulate, and effortlessly desirable. He wasn’t just a character anymore; he was an aspirational template for a post-liberalisation audience learning how to see itself on screen.

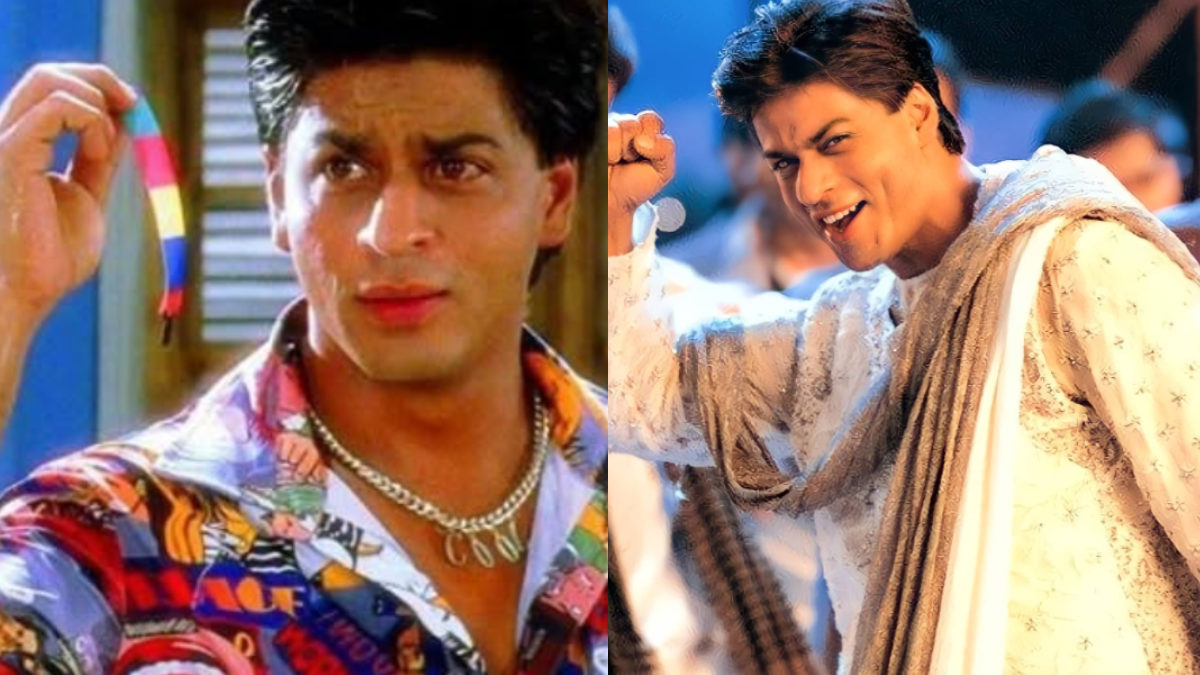

The repetition that followed was deliberate. Rahul resurfaced across genres and tones—in Zamaana Deewana, Yes Boss, and later Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham—each time recalibrated but never fundamentally altered. Rahul could move seamlessly from corporate boardrooms to college campuses, from Swiss landscapes to Delhi mansions, without the audience questioning his belonging. He was global without being alien, privileged without appearing cruel, expressive without appearing fragile.

What made Rahul endure was not narrative consistency, but emotional precision. Audiences didn’t merely empathise with Rahul—they projected themselves onto him. He represented romance that was intense yet civilised, emotional yet controlled. Even fleeting appearances, such as in Har Dil Jo Pyar Karega, relied on the name’s recall value rather than character development. Rahul no longer required introduction; recognition was enough.

By the time Chennai Express arrived, Rahul had accumulated decades of emotional memory. The name functioned almost as self-reference—ironic, nostalgic, and instantly legible to audiences who had grown up with it. Rahul was no longer just a romantic lead; he was a cultural echo.